(Una versión en español de este texto está disponible aquí)

The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor. Installation view, Museo Tamayo, Mexico City. Image: David Ayala-Alfonso.

Entering a Ragnar Kjartansson exhibition is an exercise in suspension of disbelief, in the same way that sometimes happens with a novel or a film. Not because the projects from the Icelandic artist operate within the modern Western artistic canon (although they do) that privileges art as the object, means, and end of experience, but because this body of work builds on metalinguistic exercises around Western literature, cinema, and pop music. Each work by Kjartansson, especially when involving installed video or performance, expects active or passive participation from the audience: sometimes, it is about walking through the space or positioning oneself in it, and sometimes, it is about simply being there, not leaving, allowing time to go by. Playing with temporality is key in the work of the Icelandic artist because it is precisely time and duration what articulates experience and meaning.

The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor is the title of Kjartansson’s solo show at Museo Tamayo in Mexico City. Curated by José Luis Blondet, with the curatorial assistance of Lena Solá Nogué, the exhibition brings together eight works, which include paintings, single-channel videos, performances, and installations, made over the past twenty-four years. Many of these works have previous iterations in major international venues, such as the Thyssen Museum, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Hangar Biocca, the Coimbra Biennale, Louisiana Museum, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, MoMA PS1, the Hirshhorn Museum and the National Gallery of Iceland. The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor is starkly divided into two sections: the first one features four installations/stagings with elements of immersive theater, painting, tableau vivant, and multichannel video. The second section brings together four video performance projects that play with strategies of repetition, recreation, and dilation to modify our experience of time.

A Russian Diplomat Posing as Prince Igor. Image: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

(Click here to skip the description of the works)

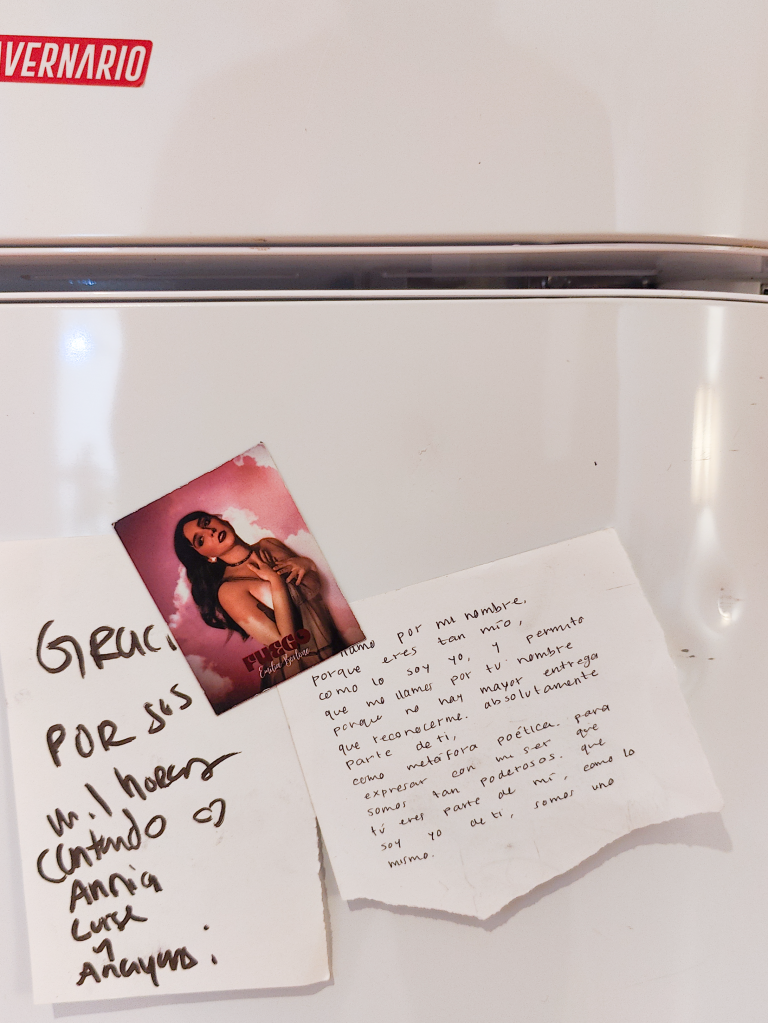

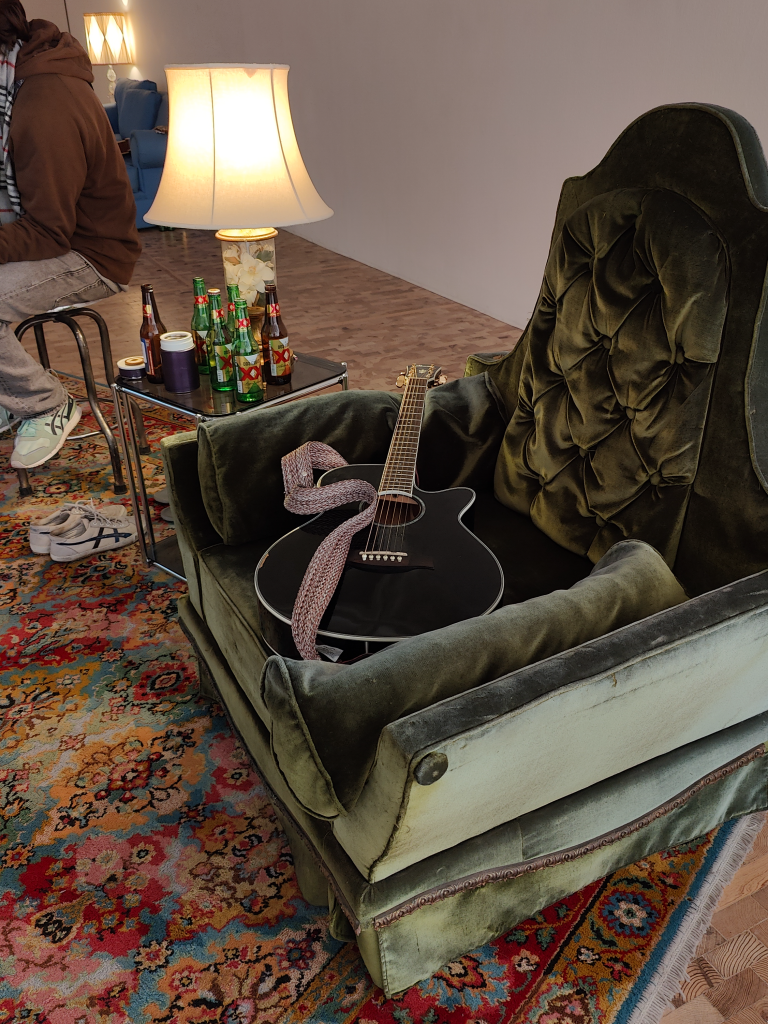

The exhibition begins with A Russian Diplomat Posing as Prince Igor (2014), a work made for a production of Alexander Borodin’s Prince Igor at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Apart from the comment on the relationship between theatrality and history, between contexts of production and deployment, Kjartansson’s gesture is one of play and irony, as he calls a diplomat from the Russian embassy in Iceland to stand in for the prince. This painting is allowed minimum attention as a massive installation/performance unfolds simultaneously behind it, and its live music attracts the gaze towards the scene with musicians, projections, domestic objects, and bottles of beer. Take Me Here by the Dishwasher: Memorial for a Marriage (2014) celebrates a biographical fact about Kjartansson, presented as a mythology of his conception: two actors from the film Crime Story (1977) stage the sexual fantasy of a housewife with a plumber, eventually giving life to the artist, as a product of their encounter off the set. A series of musicians roam a space with living room furniture, a refrigerator, armchairs, and coffee tables overflowing with empty beer bottles. The lyrics repeated by the musicians consist of fragments of the dialogues between the characters in the film; the centerpiece of the work is a projection of the film sequence, playing on both sides of a central wall. The museum didactics present us with this story, while in an apparent paradox, it mentions that biographical data is absent from the work.

Take Me Here by the Dishwasher: Memorial for a Marriage. Installation views and details Museo Tamayo. Images: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

Later, the space compels the audience to move into two adjoining rooms: the first contains the installation We Are Not Without Hope (2023), an indulgent theatrical scenography of wood and acrylic flames, over-explained in the didactics as an opportunity for the audience to become part of the scene. In fact, during the weekends, when there is a larger audience in the museum, the flames (available for sale individually on the i8 gallery’s website) serve as a formidable selfie stage. The second room presents The Visitors (2012), a nine-channel video installation, which in 2019 Alex Needham called “the best piece of art of the 21st century” (whatever that means)1. The installation brings together a series of renowned Icelandic musicians and composers2 in a mansion on the banks of the Hudson River, famous for having remained undisturbed since the early 19th century3. For about an hour, eight of the nine screens show some of the musicians separately, each in a different room, playing an instrument as part of a large musical ensemble. Eventually, some musicians switch instruments, and others progressively congregate on the the mansion’s porch, visible on the last screen. The sequence ends with the group reunited outside before they leave the mansion and head out into the countryside.

We Are Not Without Hope. Installation view, Museo Tamayo. Image: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

The Visitors. Installation detail at Museo Tamayo. Image: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

Up the ramp into the Tamayo’s reception hall we find the second section of The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor, spread out in an open room with Death and The Children (2002), a single-channel video, and Me and my Mother (2000-2015), an five-video installation where Kjartansson collaborates with his mother, the actress Guðrún Ásmundsdóttir, in an action that takes place every five years: in each video, the artist’s mother spits in his face for several minutes, and the screens show each version of this action performed since 2000. This work enunciates an attitude of rejection towards social conventions that will be repeated again and again in his work, until it becomes a leitmotif in his artistic maturity. On the opposite side of the room, on a small museum-style video video monitor, is Death and the Children, a single channel video in which the artist incarnates a figure representing death as it roams through a cemetery. The character then talks to a group of children, who interact with death without preconceptions or acting instructions. Due to the location of this work in the room, coming from a circulation space and facing Me and my Mother, it is relatively easy to overlook its presence. Adding to the problem of attention (highlighted in the introductory paragraph of this text), which complicates the placement of this specific work, the subtitles of this video are written in English, while to access the Spanish version (only as a textual transcription), a QR code is required.

Me and my Mother (detail), Museo Tamayo. Image: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

The last two works in the exhibition are installed in two adjoining rooms: the first one, Too Much Sorrow (2013-14), is a durational performance made in collaboration with The National and since presented as a video recording. The performance consists of the repetition of the song Sorrow (by the American rock band) over a period of six hours. The action took place at MoMA PS1 and is an example of a seminal strategy of the artist; that is, repetition and duration as ways of dislocating the formal and conceptual conventions of the media in which he deploys his work. The last room presents God (2007), a single-channel video in which the artist plays the role of a singer in a swing-style orchestra from the 1950s. In this video, Kjartansson repeats the phrase: “Sorrow conquers happiness” for 30 minutes, slowly and full of melancholy. The room is covered by a pink satin curtain, just like the one that serves as backdrop and decoration for the band in the video.

Due in part to its durational nature4, a work by Kjartansson can offer multiple –and quite often fragmentary– experiences. His video installations at the Museo Tamayo, which range in length from seven to seventy minutes (or can even be as long as the museum’s opening hours), are not installed in viewing conditions for a captive audience, as would be the case with film, or some single-channel video pieces. Instead, viewers are expected to move through the space at their own pace. Kjartansson understands this duration as a way of fracturing the genre conventions in video and performance5. This fracture aims to highlight the condition of the work as art, which the artist sees embodied par excellence in the genres of painting and sculpture. In fact, pieces such as God (2007) have been previously installed next to modernist paintings, as in the case of his presentation at the Thyssen Museum in Madrid. Following these ideas, we can ask a first question to the curatorial, in The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor: how does our experience of the work change when we encounter it isolated in a room?

Left: Too much Sorrow, in collaboration with The National; Right: God. Installation views, Museo Tamayo. Images: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

The question of time associated with experiencing art in a modern-Western sense appears recurrently in contexts as diverse as specialized written media and university criticism sessions. In a 2017 article6, Isaak Kaplan reviews some reasons why, ironically, the time we offer (and thus the attention we pay) to each work of art has decreased dramatically between the invention of the modern museum and our present. The analysis is traversed not only by spatial considerations and regimes of visuality organized by architecture, but also by the transformations in our attention due to the speed at which we consume digital content. This process of transforming attention, however, has a broader context.

In his book Suspensions of Perception, the American critic and essayist Jonathan Crary describes how the invention of subjective technologies of vision (such as cameras and other optical instruments) transformed the way in which we relate to the idea of attention during the 19th century. In many cases, these technologies privilege experiences of synthesis of perception; for example, the photographic fragment or frame or the political map allow us to make quick and pragmatic (though not global or systemic) readings of situations in short timespans. Later, with the invention of the smartphone (as a device that transforms audiences into content creators), the distance between the perspective of creation and that of experience collapses. The smartphone further marks a deepening of our exposure to a language of extreme synthesis, a foundational principle of digital semantics (icons, metaphors, abbreviations, etc). This context determines not only our experience of the work, but also future creation7.

Thus, Kjartansson’s work, willingly subjected to the classical mold of painting and sculpture (in examples such as God), is confronted by the economy of time of contemporary audiences. If the artist’s intention is to provide a space where the vitality spawn from duration is manifested, what curatorial gestures favor or undermine this manifestation?

One way to work through this issue is to observe how these works have been installed previously. For example, the exhibition Emotional Landscapes, presented at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, featured four video installations, including God and The Visitors. Curated by Soledad Gutierrez, the show did not confine to a specific area in the museum; instead, the works were spread throughout different rooms on two different floors. This strategy offered the audience different spaces for decompression and created opportunities for dialogue with the temporalities proposed by Kjartansson’s works. It is also possible that the formal strategies used by the artist (such as fracture, repetition, and dilation) have a more favorable context of appearance without the installation density proposed by the Tamayo exhibition. Finally, we could include in this exercise of imagination the question of how to install the works of the Icelandic artist in a retrospective context. In this sense, the intensely formal strategies employed in the work function as crucial concepts for devising a spatial proposal: dilation, rupture, fragmentation, repetition, deceleration, meta-referentiality8.

Me and My Mother (detail), Museo Tamayo. Image: David Ayala-Alfonso.

.

Another important factor in approaching the work is the relationship between construction and biographical fact presented by The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor. We can name more concretely two installations where the personal component is evident: My Mother and I, and Take Me Here by the Dishwasher: Memorial for a Marriage, are constructed upon the introduction of Kjartansson’s parents into the work. However, instead of constituting biographical instances, these installations relocate personal references to a realm of formal repertoires, more related to the artwork than to its orignal context. While the artist makes use of familiar situations that are to some extent a convention in diverse artistic media (the notion of the erotic related to the parents or the relationship between the subject and his mother, respectively) to construct an event (the “historical” or fabled event of his origin, for example), this construction takes place through multiple actions that transform the personal into self-mythifications full of irony and humor. On this, a reflection by literary critic James Wood on the use of cliché can serve to catalyze an awareness of Kjartansson’s work, which follows from the reflection on The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor:

Critic Hugh Kenner writes about a moment in Portrait of the Adolescent Artist when Uncle Charles “repairs” the toilet. Repair is a pompous verb that belongs to an antiquated poetic convention. It is “bad” writing. Joyce, with his keen eye for cliché, would only use that word knowingly. It must be, says Kenner, Uncle Charles’s word, the word he might use about himself in his fantasy about his own importance.

-Wood, J. How Fiction Works, p. 16.

Following Kenner and Wood’s ideas, we can imagine the use of these and other archetypical images in Kjartansson’s work as a conscious self-fiction, detached from the fabric of the familial. In this way, the biographical notes serve as iconic signifiers (stripped of detail to convey more general meanings), not unlike the sage of his literary, film, musical, and theatrical repertoire. In its context of presentation, in a museum in Mexico City, it is possible to see, when the curtain falls, that this construction of the artist’s character and his mythology could be opaque in this exhibition. As the American filmmaker Daniel Eisenberg explains, “Events are no longer separated from their reception…they occur simultaneously”9. Therefore, the experience of attending the exhibition (which is not the same as the experience of the slow-pace assessment performed to write about it) does not enable a critical appreciation of this self-fiction constructed by Kjartansson in his body of work. As a curator, I acknowledge the importance of offering means for such a reading, or at least to expose the audience to the possibility of its appearance, especially in contexts of presentation of this work in the Global South. The question I am left with at the end, perhaps for the curatorial team of The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor, but also for my practice and that of whoever reads this text, is how to open up this space in an meaningful way, going beyond the mere geographical and identity-driven enunciations that characterize current conversations on contemporary art.

.

.

– David Ayala-Alfonso

Mexico City, February 2024

.

.

.

Notes

- Needham interviews Kjartansson as part of a special on “the best culture of the 20th century”, in which readers of The Guardian rated a series of cultural works and events in different categories. This is one of many examples of lists and tops that are so popular today (such as Art Review’s Power 100). Far from reflecting some sort of impossible global consensus, these lists reflect the correspondence between the taste of a community or demographic and the forms and ideas developed by certain artists in their work. Kjartansson, who appears alongside other well-known artists such as Olafur Eliasson, Banksy or Yayoi Kusama –all operating in a globalized Western context– works recurrently with a cultural repertoire of European, Scandinavian and American literature, theater, music and art. In the interview, the artist ends up saying that these lists “don’t matter, except if you are on them,” accidentally (or not) underlining who are the artists promoted by such lists (and which are not) and in which cultural, geographic and economic contexts they operate.

To read the interview:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/sep/17/ragnar-kjartansson-the-visitors-best-art-work-21st-century

To access The Guardian’s feature “The Best Culture of 21st Century”:

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/sep/24/your-favourite-art-century-readers

↩︎ - They include: Shahzad Ismaily, Davíð Þór Jónsson, Kristín Anna Valtýsdóttir, Kjartan Sveinsson, Þorvaldur Gröndal, Ólafur Jónsson, y Gyða Valtýsdóttir.

↩︎ - Rokerby is a mansion in New York State belonging to the wealthy Astor and Livingston families, built in 1815. Today, Rokerby is available for rent for weddings and other social events.

↩︎ - This term is more commonly used to refer to performance works. I use it here because of Kjartansson’s combination of strategies and media, which include alluding to one medium or technique from another.

↩︎ - Kjartansson explains that “with repetition, narrative instances such as songs, concerts, and operas can lose their traditional form and become static – but vibrant, like paintings and sculptures”, and so he “[often] sees [his] performances as sculptures and videos as paintings. Excerpts from the Emotional Landscapes exhibition brochure, available at:

https://www.museothyssen.org/sites/default/files/document/2022-03/ragnar_kjartansson_folleto_en_0.pdf

↩︎ - The article, titled “How long do you need to look at a work of art to get it?” is available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-long-work-art-it

↩︎ - By this I mean that the synthesis implied in adopting these digital semantics leads eventually to a loss of detail and depth, which conditions what information is available and how it is consumed; this is a progressive dismantling of complexity that requires further analysis. On the other hand, this simplification (and the quick and synthetic reading it promotes) favors the emergence of the rehash (the refried) as a cultural product. Based on previously consumed information, it favors an archetypical reception, read with archetypical tools and yields an archetypical response from the audience. In other words, an idea is received and reacted to in the same way in the same way as its referents. In an age fascinated by novelty, it would also be necessary to reflect on the paradoxical taste for rehashing and its relationship with the culture and entertainment industries.

↩︎ - Another interesting exercise from a curatorial perspective would be to visit an example where the objective of the museographic design is just the opposite. I am thinking of the exhibition Big Heartedness, be by Neighbor by Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist , presented a the MoCA Geffen Museum in Los Angeles between September 2021 and June 2022. Curated by Anna Katz and Karlyn Olvido, the show is a delirious retrospective where environmental and immersive content is paramount, which is why the museographic design is intense, loaded with details and in which the works intersect, overlap, blend or are presented in sequence. The exhibition is extended through the introduction augmented reality didactics that activate some static materials inside and outside the exhibition. I consider this exhibition an example of a retrospective of an artist with wide international recognition, as unusual as it is formidable, and whose museographic demands are just the opposite of what Kjartansson’s work calls for.

https://www.moca.org/exhibition/pipilotti-rist

↩︎ - Eisenberg, Daniel. Unpublished Artist Talk, Middlebury College. Available at: https://www.danieleisenberg.com/alltexts/2014/8/18/unpublished-artists-talk-middlebury-college-daniel-eisenberg

↩︎

.

.

.

Ragnar Kjartansson: The Things You See Before the Curtain Hits the Floor

curated by Jose Luis Blondet with the curatorial assistance of Lena Solá Nogué

November 9, 2023 – March 3, 2024

Museo Tamayo, Mexico City

https://www.museotamayo.org/exposiciones/ragnar-kjartansson-the-things-you-see-before-the-curtain-hits-the-floor

.

.

.

Attention and distraction: Ragnar Kjartansson at Museo Tamayo by David Ayala-Alfonso is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

.

.

.

.

.

.

One response to “Attention and distraction: Ragnar Kjartansson at Museo Tamayo”

[…] (An english version of this text is available here) […]

LikeLike